VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN THE WORK OF WOMEN ARTISTS

by JANICE S. LIEBERMAN, PH.D.M

We psychoanalysts are used to speaking words, reading words, and hearing words that describe the horrific treatment of women all over the world. Presented here are a number of visual images that can help us to reflect further on this difficult topic. As they say: “One picture is worth a thousand words”. Most of these images will be difficult to look at and I have chosen to not minimize their impact by interspersing them with more neutral images. The art of the 1970’s and 90’s in particular is very concrete and “in your face”. This art does not hide behind beauty to tell its story. “Contemporary artists feel free to express visually ideas that were once forbidden, and to show what never before could be seen, as least in public.” (Lieberman 2000, p.223) These artists concern themselves with issues of human conflict and human paradox.

I intend to focus here on contemporary art, but first I want to go back as far as seventeenth century Italy to a painting done by the great woman artist, Artemisia Gentileschi, who was the daughter of artist Orazio Gentileschi. This was painted when she was just 17 years old! The Old Testament tale she depicts, that of “Susannah and her Elders” (1610), is an ancient one about sexual coercion. Susannah was threatened with execution for an infidelity she did not commit unless she consented to the Elders’ sexual demands. Susannah refused and was brought to trial. In the cross-examination that followed, the elders were shown to have lied and were stoned to death. Susannah is a self-portrait of Artemisia. We see her cringing with unbearable pain under the leering looks of the two older men. They are fully dressed, giving them power, their stare gives them power and their positioning above her gives them power. She, on the other hand, is naked except for a small flimsy cloth. Her feet are red- they have been literally and figuratively in “hot water” and are “blushing” instead of her cheeks. Her cringe is clearly that of an adolescent girl, and seems very much like the cringe of girls we know today subject to the prurient gaze of older men. It is uncanny that Artemisia herself was raped a year after painting this picture by her father’s friend Tassi,who she tried to stab in self-defense. Here too, as in the Old Testament tale, there was a trial. Artemisia grew up in a rather lawless home characterized by overstimulation and visual traumata. Supposedly she witnessed her parents in intercourse and the bloody birth of her brother, resulting in her mother’s death when she was twelve. She had posed nude for her father and had seen many nude male models. At the trial, Tassi tried to present proof that she was not a virgin when he trapped her by deducing from her drawings of male men that she had “seen” male genitalia.

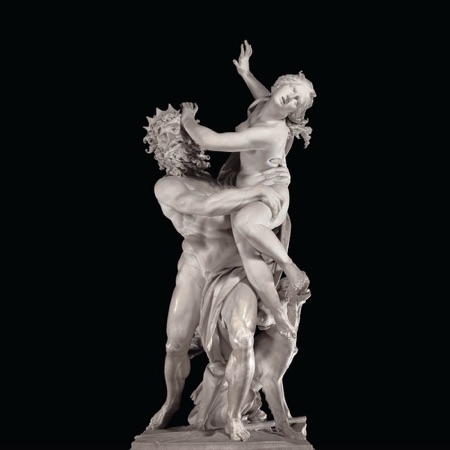

In that same seventeenth century, a number of artists depicted rape in mythological images so familiar to us that we tend to admire the art and artist and tend to ignore the violent subject matter of rape. How many of us have admired Bernini’s “Rape of Persephone”(1622) in the Villa Borghese in Rome, its baroque grace and pure white marble evoking beauty, rather than feelings of horror or indignation at her tears. Persephone was the vegetation goddess and was the daughter of Zeus. She was abducted by Pluto, the god-king of the Underworld. Similarly in the case of Poussin’s (1634) “Abduction of the Sabine Women” and Rubens’ (1618) “Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus, mass rape was considered to be part of war, all fair, and not to be thought about or challenged, very much as is the case today in too many parts of the world. We admire these paintings for their grace and beauty, ignoring their violent subject matter.

I now skip a few centuries to the 20th Century, in which women artists began to have a voice about violence in their own lives as well as in others. Here we have Frida Kahlo’s (1935) painting “A few nips:passionately in love”, done after Frida read about a woman stabbed to death by her boyfriend, who alleged that he dealt her “only a few small nips” with his knife..

This woman could be a stand-in for the artist herself. Frida’s small body was savaged by an bus accident, her life one of physical pain. According to Knafo (2009) “Frida said two things destroyed her: the accident and Diego (Rivera, her artist husband). Frida twice married Diego, who was double her age and three times her size., and she was deeply distressed by his numerous infidelities. (For example, he had an affair with her sister.) Just as she struggled with the many assaults to the integrity of her damaged body, so too she refused to give up on the tempestuous relationship with Diego, which was the source of so much heartache and pain.” (p.73) In this painting she seems to be unconsciously depicting not just the incident of which she had read, but also the sadomasochistic bond she had with Diego by showing them both bloodied. He is clothed, wearing a hat, standing over her, clearly the powerful one. The banner says “Unos Cuantos Pique Titos” (a few small nips) , the doves ironic symbols of peace.

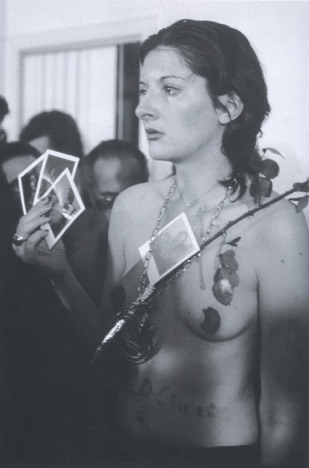

The rise of the feminist movement in the 1970’s resulted in much politicized art. A number of 20th Century women artists chose to depict violence against women in ways they said were not necessarily autobiographical. Marina Abramovic, for example, in her various performances asked her audiences to abuse her, sometimes with knives or with scissors…..

(Rhythm 0, 1974) To test the limits of the relationship between performer and audience, Abramović developed one of her most challenging (and best-known) performances. She assigned a passive role to herself, with the public being the force which would act on her. Abramović placed on a table 72 objects that people were allowed to use (a sign informed them) in any way that they chose. Some of these were objects that could give pleasure, while others could be wielded to inflict pain, or to harm her. Among them were a rose, a feather, honey, a whip, olive oil, scissors, a scalpel, a gun and a single bullet. For six hours the artist allowed the audience members to manipulate her body and actions. This tested how vulnerable and aggressive the human subject could be when hidden from social consequences. By the end of the performance, her body was stripped, attacked, and devalued into an image that Abramović described as the “Madonna, mother, and whore”. Additionally, markings of aggression were apparent on the artist’s body; there were cuts on her neck made by audience members, and her clothes were cut off of her body. Abramović’s art also represents the objectification of the female body, as she remains motionless and allows the spectators to do as they please with her body, pushing the limits of what one would consider acceptable.

The women artists I discuss next give us windows into the shattered psyches of those who have been abused and raped. Unlike the images of Artemesia, Bernini, Poussin, Rubens and Kahlo, the male perpetrators are not depicted. Ana Mendieta (1973) recreated the crime scene of the rape and murder of fellow University of Iowa student Sara Ann Otters. For the performance, spectators found Mendieta crouched like this, bloody and still, naked from the waist down. She did additional tableaux of rape that year. She did not announce them but let them be discovered by unsuspecting passersby. In one she spread blood on the sidewalk and observed people walking on by, indifferent to the violence they had just seen.

A number of Mendieta’s performances which she photographed depict she herself as abused. You may know that in her personal life she either jumped or fell out of a window and died. Her partner, the prominent artist Carl Andre, was brought to trial, but exonerated from having committed the brutal act.

Also autobiographical are the photos and films of Nan Goldin, who had a series of sadomasochistic relationships with men. Here in “Nan One Month After Being Battered” (1984) she shows what was a considerable improvement upon her physical condition after have been battered.

In 1980, less horrific, she photographs “Heart-shaped bruise”, as if bruises and affairs of the heart necessarily belong together. Goldin, in her ongoing film series “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency” (1981- ) said that: “I wanted it to be about every man and every relationship and the potential of violence in every relationship”. I find this to be sadly accepting. Nevertheless, showings of her photos are used to effect change.

I saw Sue Williams’ (1992) autobiographical sculpture “Irresistable” on the floor of the Whitney Museum. The pain of the crouched figure and the writing on it go right to your heart. She cringes as if in a catatonic cocoon. The words of her batterer are: “YOU DUMB BITCH. I DIDN’T DO THAT. HAVE YOU BEEN SEEING SOMEONE SLUT. I THINK YOU LIKE IT MOM. LOOK WHAT YOU MADE ME DO. ETC.”

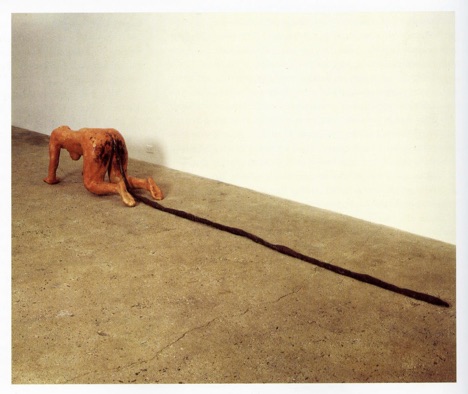

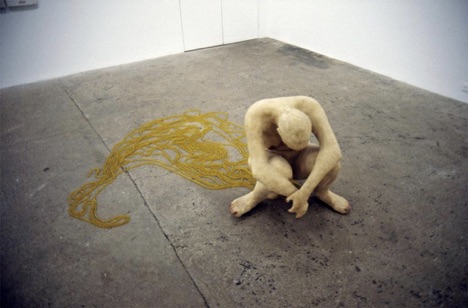

The woman artist in my opinion whose oeuvre most poignantly depicts violence against women is Kiki Smith. Her father was the prominent sculptor Tony Smith. His three daughters all became artists. Kiki says little about her relationship with her father……I saw “Tale” (1992 ) also on the floor of the Whitney Museum. A naked woman crouches on the floor, her rear end covered with excrement and leaving a long t-a-i-l that is concrete evidence of the t-a-l-e she could tell. Art critic Linda Nochlin (2015) reports a “visceral shock”, “I still remember the intensity of the feeling, as though the bottom had dropped out of the sedate world of the gallery and my own place in it, to put it more physically, I felt it in my guts” (p.290)

Kiki did “Bloodpool” (1992) in the same year. What could be a more wretched image?

And in the same year “Pee Body” (1992), a humiliating image of an abused woman, an image of abjection as conceptualized by Julia Kristeva in her Powers of Horror . Evidently some male art critics wrote that Smith degraded art itself by calling attention to such low bodily functions as peeing. I want to read to you some lines written by Kristeva about “abjection”: “The body’s inside… shows up in order to compensate for the collapse of the border between inside and outside. It is as if the skin, a fragile container, no longer guaranteed the integrity of one’s “own and clean self” but, scraped or transparent, invisible or taut, gave way before the dejection of its contents. Urine, blood, sperm, excrement then show up in order to reassure a subject that is lacking its ‘own and clean self’. The abjection of those flows from within suddenly become the sole “object” of sexual desire- a true “ab-ject” where man, frightened, crosses over the horrors of maternal bowels and, in an immersion that enables him to avoid coming face to face with another, spares himself the risk of castration”. (p.53) A compelling explanation of rape, isn’t it?

The early 90’s were a time of unearthing tales of violence during wartime. Judy Chicago of “The Dinner Party” fame worked on a book called The Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light (1993). In “Double Jeopardy: Everybody Raped” she found that in the camps, not just the Nazis but the liberators too- American, British and Soviet soldiers, raped women Bergen-Belsen survivors.

Kara Walker, one of our most prominent African-American women artists, chronicled in her powerful silhouettes the sexual misuse and abuse of black slave women by their white masters on Southern plantations during those infamous years of American history. This is from her incredible mural (1995)“The Battle of Atlanta: Being the Narrative of a Negress in the Flame of Desire”. Notice the flung chicken leg.

Walker’s work bitingly satirizes the white man’s desire for black women: “I like my coffee like I like my women, any number of combinations, ‘hot, black and sweet’, ‘black with a touch of cream’. The black female body as both subject and repository of sexual fantasies, phobias, and taboos prevails as the locus of a major portion of Walker’s work with the hope that as she exposes it, it will lose its menacing power.

Fast forward to today…. The daughter of two of our colleagues in New York, 21 year old Emma Sulkowicz, a performance artist, decided to not forget about and keep “hidden under the mattress” a date rape incident at Columbia University. For her senior thesis, called “Carry that Weight”, she carried the offensive mattress wherever she went and even disregarded university authorities by bringing it with her to graduation. University President Lee Bollinger turned away from her, refusing to shake her hand. She was harshly criticized for creating publicity that could promote her career, but she did bring awareness to the public about the prevalence of date rape, a backlash to the growing independence and success of young women.

I choose to end with this glorious image of a bronze sculpture by Kiki Smith called “Rapture” (2001). It recalls the story of St. Genevieve, who saved her people from Attila the Hun. She is standing erect, the wolf is powerless, lying on the ground. Smith also refers to the story of Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf. Art critic Denson (2015) has written that :

“Kiki Smith’s 2001 bronze sculpture “Rapture” embodies a woman stepping out of the upturned corpse of a wolf that had devoured her. Whether or not the work’s title is an alliterative play on words (the rupture of rape=woman’s “rapture”), Smith has embodied every woman’s wish for a time when women have conquered rape” (p.15)

She is not crouching, bent over or beseeching. She shines in the light just as women all over the world will shine as a result of efforts we are undertaking to combat violence against women.

IMAGES:

Artemesia Gentileschi (1610) “Susannah and her elders”

Bernini (1622) “Rape of Persephone”

Poussin (1634) “Abduction of the Sabine Women”

Rubens ( 1635-7) “Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus””

F. Kahlo (1935) “A few small nips: passionately in love””

M. Abramovic (1974) Rhythm O

A. Mendieta (1973) “Rape, Murder Scene”

(1973 ) bleeding eye

N. Goldin (1984) “Nan one month after being battered”

(1980) “Heart-shaped Bruise”

S Williams (1992) “Irresistable”

K. Smith (1992 ) “Tale”

(1992) “Bloodpool”

(1992) “Pee body”

J. Chicago (1993) book Holocaust Project: from Darkness into Light “Double Jeopardy”:

“Everybody raped”

K. Walker ( 1995 ) “A Negress on the Flame of Desire”

E. Sulkowicz (2014-5) “Carry That Weight”

K. Smith (2001) “Rapture”