Velasquez “The Rokeby Venus”

S. Freud (1923) “The first ego is the body ego”

What is meant by the expressions “beauty is only skin deep”? “She is as beautiful on the inside as she is on the outside”? “I’ve got you under my skin”?

Eva Hesse “Sans II”

Functions of the skin:

To cover and protect your insides: skeleton, blood, body liquids, nerves, muscles, organs, EMOTIONS

To serve as a gateway to what gets in and what gets out

To expose you to the outside world: others’ touch and others’ looking at you

Mary Cassatt “The Young Mother”

To contain memories: mother touching you, bathing you, cleaning you, nursing you, cradling you, rocking you, covering you.

Blankets often contain the transition from mother to the outside world- a symbolic second skin.

What does your skin feel like to you? soft, relaxed, irritated, itchy?

What does your skin look like to you? smooth, dry, cracked, wrinkled, spotted with blemishes?

Memories of skin from infancy, childhood and especially adolescence are brought forward into adulthood as well as traumatic events: measles, chickenpox eczema, cuts, burns, acne, infections.

Some ritually cut their skin as a way to repeat or deal with early trauma by trying to control it.

Meanings of the Skin

Didier Anzieu (1989) skin ego/skin envelope

The skin ego was originally a “common skin” shared by mother and child. It is eventually surrendered as the internalization of a supportive mother develops. When things are going well there is a sense of security, providing a narcissistic envelope. When things are not going well, there is an “envelope of suffering”, bringing shame.

Elizabeth Bick (1968) psychic skin/concrete skin

If the mother cannot help the infant to contain there is a frantic search. Skin connections serve as a primary bodily container. If there is a disturbance in the primal skin function, a “second skin” formation replaces dependency on the object with pseudo-independence (based on muscularity, tattooing, etc. rather than identification with a containing object).

Ellen Sinkman (2013)

“As Freud stated in (1905) (p. 168), the skin is the erotogenic zone par excellence. Skin contact which began for the infant in the feeding situation was accompanied not only by the pleasurable, internal, self-preservative satiation of hunger, but also by inner and outer skin stimulation and sensuality. Being held and being bathed are among additional instances of excitement and perhaps bliss for an infant. Overstimulation and rough handling are the other possibilities of skin contact, serving as templates for future use and abuse of one’s skin.”

Alessandra Lemma (2010) draws on a range of theoretical frameworks, predominantly British object relations as well as Lacan and Kristeva.

The Skin in Body Dysmorphic Disorder

To those afflicted, different parts of the body feel ugly and they have difficulty looking at them and are sometimes mirror avoidant and/or agoraphobic.

Jim Dine “Wolfman’s Dream”

Phillips (1996) believes that the Wolf-Man suffered from BDD (which Freud never mentioned in his case history). Brunswik, the Wolf-Man’s second analyst, that he neglected his daily life because he was so engrossed in the state of his nose, its supposed scars, holes and swellings. He obsessively looked at a little mirror he had in his pocket for that purpose.

“Oh, the necks. There are chicken necks. There are turkey gobbler necks. There are elephant necks. There are necks with wattles and necks with creases that are on the verge of becoming wattles, There are scrawny necks and fat necks, loose necks, crepey necks, banded necks, wrinkled necks, stringy necks, saggy necks, flabby necks, mottled necks. There are necks that are an amazing combination of all of the above. …..The neck is a dead giveaway. Our faces are lies and our necks are the truth.” (p.5)

Nora Ephron (2006) I Feel Bad About My Neck

Alessandra Lemma (2009)

“For as long as he could remember, Mr. S had hated several parts of his appearance.. As an adolescent he had resorted to “DIY” surgery in an attempt to alter a particular facial feature. The locus of his body hatred had shifted over the years, mostly affecting his experience of facial features, but as an adult this concern had spread to the appearance of his foreskin. Although in sessions he would refer in a general way to disliking the appearance of his penis, his distress and anxiety were specifically focuses on his foreskin. The ritualistic behavior that was time-consuming (e.g. regularly checking his penis for extended periods, covering up his neck with scarves even at the height of the summer) and led to marked social isolation and obsessional rituals related to his appearance” (p.766)

Rineke Dijkstra “Kolobrzeg, Poland, July 26, 1992” and “Olivier Silva, The Foreign Legion, August 10, 2000

The Consulting Room

Janice S. Lieberman (adapted from Lieberman, J.S.in Frosch (ed.) 2012)

As treatment began, Amanda began to visit a series of dermatologists and was particularly upset by one who “assaulted” her by biopsying several small bumps on her chest. She experienced this as a kind of rape. On some level I believe that she was experiencing me as attacking her and invading her, but she protected herself from awareness of this through displacement.

Amanda had a slight case of acne and became obsessed with it. She stood in front of the mirror for hours looking at and squeezing the pimples, thus making the irritation worse. She tried all kinds of creams on her face, then looked up their ingredients on the Internet, concluding that they were “bad” for her. She argued with each dermatologist about the safety of the creams and antibiotics they prescribed. She came to me as “referee” and spent countless hours on the phone about whether these products would cause her permanent damage. Amanda was concerned that with her treatment for acne she had done “permanent” damage to herself, had permanent scars.

A classic understanding of her problems would be one of castration anxiety and fears of genital damage. My treatment of her was along the lines described in my (2000) book: I spoke with her quite concretely, since she was unable to speak of her issues as if they had any psychological meaning. She wanted me to see her face each session and to let her know what I thought: was it better or worse. She came in suffering. “I’ve had a miserable weekend. I have driven my boyfriend crazy”. I thought that she wanted to drive me crazy too. I was called upon as another “mirror” to try to soothe the bad image she had of herself. She would come in and confess (in a highly dramatic manner):”I was BAD”, meaning that she had picked her pimples. It was high drama, and I was quite aware of the role I had been cast in. I was also willing to play that role, since it confirmed the hypotheses I had developed about working with body narcissism. The kind of aversive countertransference I might have had fifteen years prior (“I cannot believe that I am listening to such rubbish!”) was quite muted due to my experience with so many of these patients, what I regard as the patients of our time.

I continued to look at her face as she came in and commented about the redness or lack thereof of her pimples. I asked her if she had picked them. My concrete interventions and my taking her complaints seriously began to calm her down after many weeks. She needed reassurance that she had not permanently damaged her face or body. I did not offer it but did offer attention and talking. My task, as I saw it, was to look, to be verbally descriptive, affirming, and to avoid any seductive or personal, non-professional compliments or vocal intonations.

I used my psychoanalytic lens to understand what was going on underneath. She was quite conscious of envying a pregnant friend, the envy being so great that she could not see her friend anymore. As is my custom from time to time to test the current level of my patients’ thinking, I tried a metaphoric statement: “The bumps on your face may represent baby bumps”. She had no response to this, as if it were nonsense. At another time, I interpreted “picking your face is a substitute for picking on yourself” but this too went nowhere with Amanda.

Continuous work along the lines of my looking and talking to Amanda yielded positive results. She stopped traumatizing her skin and it eventually healed.

Janice S. Lieberman (unpublished)

Steven came into therapy in order to understand why his business had not prospered. Increasingly in his sessions he began to complain about rashes and bumps appearing at moments of stress on his face, mainly on his nose. He visited several dermatologists who gave him different diagnoses and different creams and antibiotics. It seemed to me that he had a slight case of psoriasis, but not being medically trained I sent him to a dermatologist to diagnose him. Like Amanda, he wanted me to look at his face and give him feedback as to whether the redness was so bad that he should stay home and not go to work. His conscious concern was about being seen. Yet he had a profound need to be seen and to have what he looked like put into words.

One day he sent me a photo of his face with the rashes on his nose and wrote:

“This is NOT from scratching squeezing scrubbing…it just happens and hurts like hell. And guess freakin’ what? This is yesterday…today all the red spotting has spontaneously exuded double the blood and therefore the redness. So imagine it. I’m too vain to photograph it.”

Steven’s concern about his skin and its appearance was fueled in part by a need for me to carefully look at him and verbally communicate with him about what I saw. He was the child of a drug addict left on his own most of the time and did not receive the kind of close bodily attention and care most children get.

TATTOOS AND CUTTING

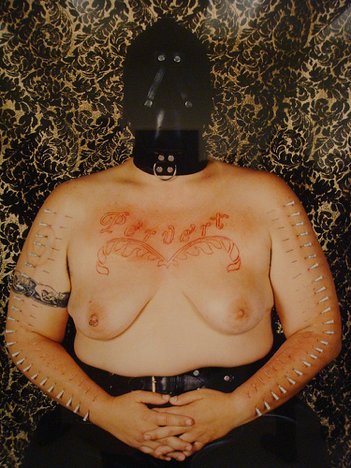

Catherine Opie – TATTOOS

How much is cultural?

How much is carving an identity?

How much is pathological?

Examples: Tattoos of nipples for reconstructed breasts

Second and third generation holocaust survivors’ tattoos of concentration camp numbers

Uta Karacaoglan writes that during an ongoing analytic process tattooing projects a visual image in the transference – like a snapshot – to form a backdrop for the most salient unconscious inner conflicts arising. The tattoo is a visual symbolization of a taboo transgression and simultaneously activates the same through an act of self-injury that resembles the magical ritual acts of indigenous peoples’ use of tattoos. Tattooing represents a marginally successful attempt to create a transitional object by conjoining the actual manipulation of the skin with the symbolic creation of an image. As the tattoo remains a part of the body, it documents a collapse of transitional space. The image then acts like a “patch” to repair holes blown into Winnicott’s “potential space” and to reconstruct it.

CUTTING THE SKIN

Africa- cuts on face, scars

Jewish circumcision

pierced ears

PLASTIC SURGERY

Alessandra Lemma (2010) proposes that in order to approach the psychic function of various types of body modification (piercings, tattoos, cosmetic surgery), it is vital to understand the unconscious fantasy that drives the compelling pursuit of body modification. She outlines some of the fantasies that she has observed in her patients who modified their own bodies to illustrate how the body becomes the canvas for the expression of psychic deficits and conflicts and its modification becomes the solution to psychic pain. She draws upon Almodovar’s film, “The Skin I live In”, for illustration.

Gunter Brus “Self-mutilation” (1965)

Marina Abramovic (1975) cut a star into her stomach in “Lips of Thomas”

Catherine Opie “Self- Portrait/ Pervert” (1994)

Orlan “The Reincarnation of Saint Orlan (1990)

Janice S. Lieberman, Ph.D. is a Psychologist/Psychoanalyst in private practice in New York. She is an IPA Training and Supervising Analyst, Fellow and Faculty Member of the Institute for Psychoanalytic Training and Research. She served on the Editorial Board of the Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association for many years and is a Book Review Editor of the PANY Bulletin. She is the author of Body Talk: Looking and Being Looked at in Psychotherapy (Jason Aronson 2000) and has published and presented widely on topics of gender, body image, deception, shame, greed and psychoanalysis and art. She has been a Docent at the Whitney Museum of American Art for 25 years.

Wonderful new arena!

I love this new museum! It’s so creative, informative and interesting.

dd

Fascinating way to see the person as he or she wants to be seen. The non-confrontational acceptance of what appears to be a symptom leads to a better understanding of the compromise formation that it represents and gradually allows the analyst to “get under the skin.”

I think what you composed made a lot of sense. But,

consider this, what if you were to create a awesome headline?

I mean, I don’t want to tell you how to run your website, however suppose

you added something that grabbed folk’s attention? I mean The Skin You Live In: Intrapsychic Meanings and Concrete Enactments by Janice Lieberman | The Virtual

Psychoanalytic Museum is a little plain. You could glance at Yahoo’s front page and note how they create news titles to get

people to open the links. You might add a related video or

a pic or two to get people interested about what you’ve got to say.

In my opinion, it could bring your website a little livelier.

could you tell me more about how to get out our work? I have a lot to learn about the internet!! I welcome all the input we can get. Nancy Goodman nrgoodmanphd@gmail.com

I appreciate the new museum very much.

It is interigging and thought provocative. with gratitude,

Mali Mann